Highland Center for the Arts Highland Center for the Arts presents “A Sense of Place,” paintings by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol and photographs by Richard J. Murphy, through Nov. 12, at The Gallery, 2875 Hardwick St. in Greensboro. Hours are: noon to 4 p.m. Wednesday-Sunday; call 802-533-3000, or go online to

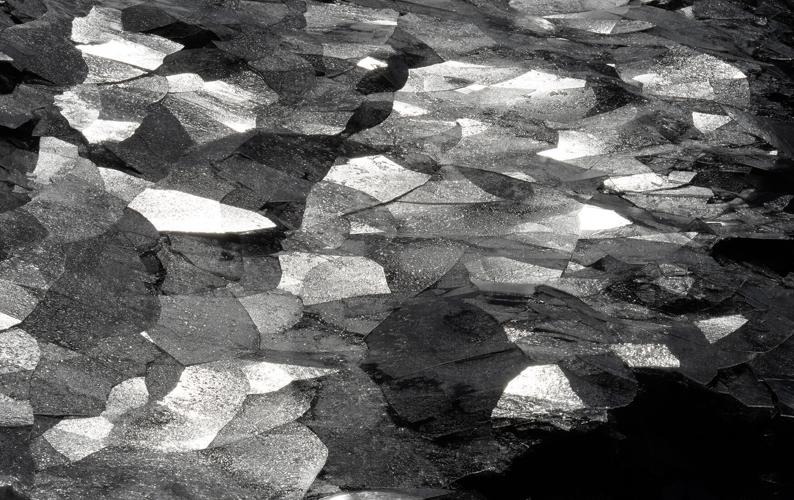

highlandartsvt.orgAn Alaskan mountain reflected in ice studded seawater; a trail of pale yellow butterflies echoing the play of yellow sunlight on the sea; tide shattered sheets of ice — sense of place may be in a geographic setting. It may also be in a more abstract, cerebral place.

“A Sense of Place,” an exhibition featuring paintings by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol and photographs by Richard J. Murphy, opened last week at Highland Center for the Arts in Greensboro. In their different media, the siblings, who live on opposite sides of the country — Murphy in Alaska and Tyrol in Vermont — each have a distinct focus in their work.

Together, their works connect and converse, often in water and rock — Murphy’s rugged Alaskan mountains, Tyrol’s rock outcrop in Lake Champlain; Tyrol’s mythical siblings afloat in an Icelandic fjord, Murphy’s melting ice.

“They are both masters of their craft. They are passionate portrayers of the essence of and their reverence for the world they inhabit,” said Maureen O’Connor Burgess, HCA gallery curator.

“At first glance, Richard’s sense of place is more concrete, more geographical, captured by his discriminating eye and shutter speed. He captures the awe of the constant and of the changing. The minute to minute, day to day as seen in the mountain series captured from his back yard and then over longer time the river, the ice, in ‘The Melt.’”

“Adelaide’s sense of place is, to me, more ethereal. It, too, is spectacular. Her eye is also keen and discriminating but her source is not just in the seeing, but the feeling and the knowing, and the wanting to know. Her “Sense of Place” is more insinuated — the natural world that can’t be measured or defined,” said Burgess.

Besides painting, Tyrol, who lives in Plainfield, has concurrent careers in small and large-scale illustration. On the small side, her precise natural history illustrations are in newspapers and magazines including the Northern Woodlands. On a large scale, she is longtime co-owner of Oliphant Studios in New York, and hand paints huge backdrops for photographic shoots and other scenic projects.

Tyrol notes that she has found a personal sense of place with her artwork that is between the methodologies of her commercial work. In this place, she brings together big brushes and broad strokes and also her subjects of nature and its organisms.

Tyrol’s paintings at HCA connect to particular places she has recently been — “Frey and Freya” in Iceland, “Quadrant” and “Three Graces” Lake Champlain, “The Coming of Light” Cape Cod. In them are other layers of perception. In “Three Graces” a trio of diaphanous feminine figures approach between water and sky.

“I believe the power of nature lies beyond the caliper, and in that liminal zone between mind and matter — there can be a delicate bridge leading to a deeper understanding of life,” Tyrol says in her artist’s statement.

Wallace Stevens’ poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” with its haiku-like stanzas, is on one wall, accompanying 13 blackbird paintings and drawings by Tyrol. As in Stevens’ poem, there is more to each piece than just birds — a flock on a wire, a landing in process, a murder of crows overhead. Tyrol framed them with mirror in each one — crows like shiny things, and viewers find glimpses of themselves in looking at the birds.

The avian also makes an appearance in one of Richard Murphy’s photographs. In “Rising Black Bird, Alsek Lake,” a solitary bird flies in a landscape of floating ice, glacially scoured rock and jagged mountains. The photograph is in Murphy’s “The Melt” series — images of ice and water and Alaska’s breathtaking landscape, which is now undergoing accelerated climate driven change.

Murphy has lived in Alaska since 1985, when he moved to Anchorage to work as newspaper photojournalist, a career that has included being on the Anchorage Daily News team that won a Pulitzer Prize for public service.

“‘The Melt’ is really my statement about climate change. In Alaska, we are experiencing the vagaries of climate chaos. One of the primary indices of climate change is the melt of ice,” said Murphy, noting that some of Alaska’s ice in the permafrost layer has been there since the Pleistocene ice age and is now melting.

“Seasonal ice is coming later, leaving earlier, and is not as thick in between. And in Alaska, that really affects life,” he said.

In “Castner Glacial Arch, Alaska Range,” an ice cave with geologic-like striations, the photographed roof segment has since collapsed. Methane bubbles, from deep organic matter, are for the moment suspended in thick dark ice, soon to be released. In Murphy’s nine-panel “Crack,” a distinct white line speaks to ongoing change.

“None of the ice in these photographs remains in the state you are viewing them. They have all gone to fluid or are in the process of doing so,” says Murphy in his artist’s statement.

One group of Murphy’s photographs are of Mount McHugh, a 4,000-foot-high peak, literally in his backyard. The mountain’s mass is constant, but its character is dramatically dynamic, cloaked in mist, snowfields reflecting sunlight, wind sweeping clouds around its heights.

“This is what gives me a sense of place, the geographical anchor that makes me know that I’m home,” said Murphy, standing with the mountain photographs.