In a scene reminiscent of Dicken’s “A Christmas Carol,” every year, the children of the town of Danby receive gifts from a wealthy benefactor who was once a miserly tyrant. He drove his workers mercilessly, forcing them to work from dawn to dusk. He forbade them to carry pocket watches, lest they become clock-watchers.

Nevertheless, since 1901, the Danby millionaire’s estate provides for an annual Christmas party during which every child in town receives a gift and an orange. A personal revelation in the Holy Land changed the Danby native from a Scrooge to a Santa.

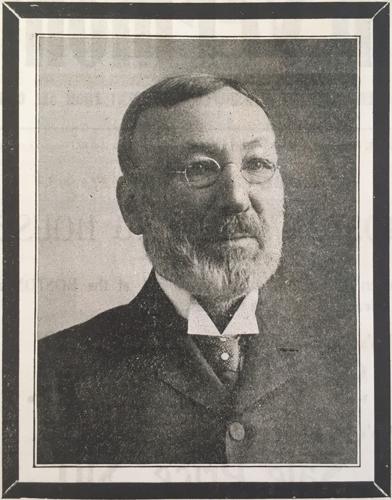

Silas Lapham Griffith was born on the family farm in 1837 where he worked when not attending the local school. He had an affinity for books and learning, according to Ann Rothman’s 2022 biography. When age 16, he began employment at a local mercantile in Danby, saving enough money to attend a private academy in New Hampshire for a year. With his plans for a teaching career sidetracked by a national financial crisis, he was able to secure local funding to open a general store in Danby.

Storekeeping came naturally to young Silas. He came from a long line of shopkeepers on his mother’s side of the family. Almost immediately, he proved his innate ability for business and expanded his store until it was with three floors, for a time, the tallest building in southern Vermont. Griffith needed a reliable supply of water for his business interests and built a gravity-fed water system, which eventually was purchased by the town.

While a successful merchant, Griffith made his fortune in the timber business. Ever keen on taking advantage of foreclosures, he eventually owned 50,000 acres of forest, acquired piece by piece. He manufactured lumber and charcoal in a company town called Griffith (from 1891–1905) — which later became known by the name of the neighboring town of Mount Tabor. With money from the sale of his store, he bought 9,000 acres of timber in Mount Tabor. It was suggested some of his land acquisitions were made by less than legal means — that he resorted to bribing sheriffs and other local officials to help him persuade uncooperative landowners to sell him their property at terms favorable to Griffith.

As his lumbering operation grew, so did Griffith’s paternalism. He built two boarding houses for his workers and offered free room and board. He even had a stockman to oversee the supply of beef and pork. Rothman describes the accommodations he provided for married employees. “The married couples lived in cottages with gardens. Some of them played tennis. They’d set up a net and played with small Wright & Ditson racquets. Near the cottages, there was a school for the kids and a big general store, the S.L. Griffith Co. General Store that housed a post office.”

His workers, however, were often in his debt, and some never became solvent.

By 1880, according to Rothman, Griffith had built a steam-operated mill that could cut 20,000 board feet of lumber a day. There were also 30 charcoal kilns, producing fuel for industry — a product as profitable as lumber. This was the era before the general use of oil and gas, and the production of charcoal was important to developing the Griffith fortune. Rothman notes that annual output of Griffith’s kilns totaled 1 million bushels. To manufacture this prodigious quantity required 20,000 cords of wood.

During his lifetime, according to Rothman, Griffith’s business enterprise was the largest in the state of Vermont and employed over 600 workers. He was Vermont’s first millionaire.

At a certain point in his driven life, Griffith had a change of heart. His first wife had divorced him for reasons of intolerable cruelty, but he found love again and married a woman of culture and refinement and began using his wealth to broaden his horizons. Ann Rothman noted that, by 1882, Griffith became more interested in spending money than acquiring it.

He traveled extensively. His obituary in the Burlington Free Press states he visited “Mexico, Cuba, Europe, Egypt and the Holy Land.” He built vacation homes where he had some of his largest timber holdings, Mount Tabor and Groton. Building ponds at both locations, he stocked them with trout raised at his own hatchery, the first in Vermont. He exported fresh fish to various resorts as well and invited his guests to fish for them.

In his early 60s, Griffith began to provide for the children of Mount Tabor with an annual “Christmas Tree” starting in 1901. It began as a treat for the children of his employees but soon became a celebration for all the children in Danby between the ages of 2 and 12, and continues to this day. According to a 1901 report in the Burlington Free Press: “When Griffith was in Palestine after his visit to Jerusalem and Bethlehem last winter, it occurred to him that he would give the children of Danby and Mount Tabor just such a Christmas tree as he believed Christ would give them were he on Earth and in this place.”

At the first such event, “Miss A.S.M. Bushee sang a solo titled “Holy Night” and there were recitations given by the children as well as several pieces sung by them. Griffith gave them the particulars of his visit to the church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. He also gave them a history of St. Nicholas. In the church were three spruce trees that reached nearly to the ceiling. On these trees were upwards of 500 presents.”

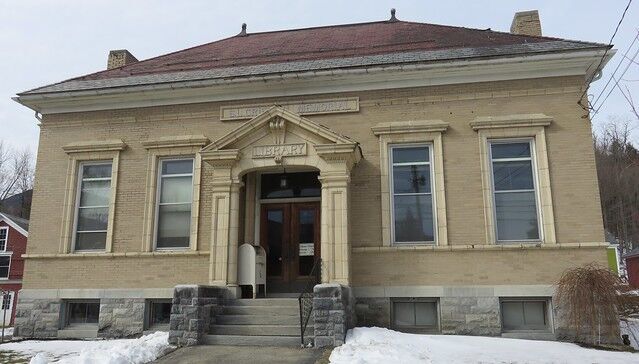

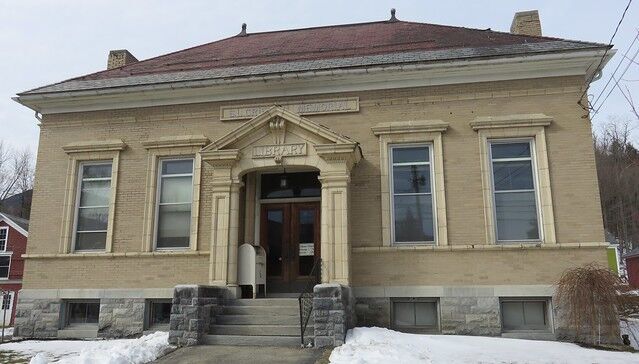

To this day, a Christmas party is held at the Congregational Church, itself a gift from Griffith, as is the Silas L. Griffith Memorial Library built in 1903. After refreshments and after singing Christmas songs, there is the presentation of the Christmas tree.

Presents for each boy or girl are arranged in the boughs of a large Christmas tree and, as each child’s name is called, he or she steps forward to receive a gift and an orange. In the early years, it would very likely be the first time the boy or girl would have seen or tasted this fruit which was still considered exotic. Eventually, parents were consulted about the child’s preference for a toy. Often, the gift from Griffith’s Christmas tree was the most expensive present a child received. In his will, Griffith created an endowment that has allowed the practice to be continued indefinitely.

A 1989 account in the Bennington Banner suggests that, in the early days, it was the only Christmas some children had. Upon the death of Griffith’s second wife, Katherine, her bequest added more to the fund, which kept it on solid footing throughout the Depression. The Banner reporter noted: “Some of the parents bearing pajama-clad toddlers into the church were once recipients of a new toy themselves. Traditional carol singing starts off the festivities and then the minister makes a few remarks about the man behind it all.”

Griffith died in 1903 near San Diego, California, at his West Coast residence, “The Palms.” He had accomplished a great deal in his 66 years. In addition to being a major industrialist, he also served in the Vermont Senate. In California, he managed an orange grove. His death certificate named a skin condition called pityriasis rubra as the cause of his demise. It sometimes resembles advanced syphilis, which gave rise to scandalous rumors among those in Danby who felt they had been misused by his aggressive business practices.

This official document lists his occupation as “Capitalist.” Nevertheless, his reputation is redeemed every yuletide in Danby.

Paul Heller is a writer and historian from Barre