One winter day, while teaching a winter ecology class, I pulled on waders and rubber gloves, grabbed a catch net, and led my “Minibeasts of the Stream” program, discovering a rich variety of insects in the frigid waters of Kedron Brook in South Woodstock, Vermont.

Insects are abundant in winter streams because they are able to find food and, on most days, the water is warmer than the surrounding land. Many species hatch in time to consume autumn leaves and the bacteria that grow on them. Winter light penetrates through naked tree crowns, allowing diatoms (single-celled algae) to flourish on rocks, becoming food for grazing insects.

Insect species that rely on streams for some stage of their life cycle overwinter in the forms of eggs, larvae or nymphs. Most insect life cycles include egg, larva, pupa and adult. Many aquatic insects, however, move from egg to nymph to adult, with the nymphal stage developing through several instars.

Crane flies, caddisflies and riffle beetles overwinter as larvae, while stoneflies, mayflies, dragonflies and damselflies survive as nymphs. Black flies overwinter as eggs, hatching sequentially by species from late winter through summer. Most mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies develop in a single season, with mayflies living only a few days as adults. (The names of true flies — in the order Diptera — are spelled as two words, as in “crane fly.” Those that are not true flies are one word; for example, “caddisfly.”)

Winter survival requires moving around in the stream to avoid frigid waters, but the cold-tolerance of some aquatic insects is truly impressive: mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies can survive body temperatures as low as 19.4°.

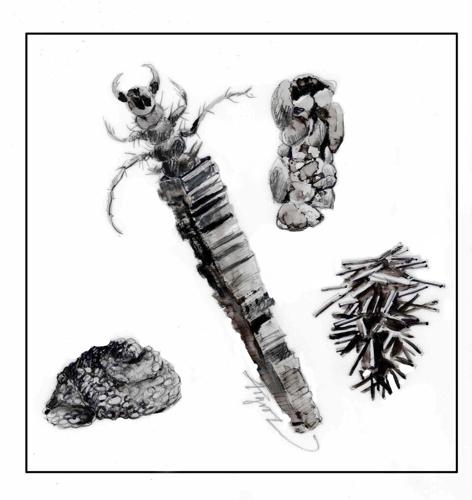

Crawling amid the rocks, soft-bodied caddisfly larvae weave ingenious silk tubes into mobile dwellings. Depending on the species and age (some larvae use different materials as they grow), they typically glue sand, leaf pieces or small sticks onto the outsides of these silk tubes. Brachycentrus, the log cabin caddisfly, fashions a square home of minute plant parts. One genus, the Helicopsyche, was originally classified as a snail because its spiral case of minute sand grains is shaped like a nautilus.

Crane flies overwinter as 2-inch larvae that absorb oxygen through the skin and have an appendage that serves as a snorkel. In springtime, they transform into non-biting, nectar-sipping, “mosquito hawks” that hover in shady places or flutter on screen doors at night. One of the most strikingly beautiful insects, the black-winged damselfly, also called ebony jewelwing, spends winter stalking prey as an aquatic nymph before transforming into an elegant adult during the growing season.

Turn over a rock in a winter stream, and you will likely find stonefly or mayfly nymphs, which, along with the water penny (riffle beetle larva), have flattened shapes, which allow them to cling closely to rocks in fast water. This 1- to 3-millimeter space around the rock, the boundary layer — where friction between rock and water slows the current significantly — becomes thicker in winter because cold water is more viscous.

Generally, mayflies are herbivorous and stoneflies, carnivorous. Sifting through submerged vegetation, however, you may encounter a nymph of one of the giant stoneflies, genus Allonarcys, which feed largely on plants and plant debris. The 2-inch nymphs may take several years to mature.

And then there are marvels of nature that outdo the most stalwart winter-lovers among us: awe-inspiring adult winter stoneflies that creep along the frosty snow in search of mates. On sunny days from January through April, the nymphs emerge from streams and transform into tiny (½-inch) adults with dark brown to black exoskeletons that absorb the sun’s heat. Their body fluids contain a natural antifreeze of sugars, proteins and glycerol.

Less likable, perhaps, are black flies, of which New Hampshire and Vermont each harbor more than 50 species. Some overwinter as eggs that hatch into larvae in early springtime. Others overwinter as larvae, forming pupae from which adults emerge in April and May. The tiny larvae have bulbous butts that they anchor to submerged objects using silk threads, sticky saliva and more than 100 hooks arrayed in a radial pattern. Sieve-like hairs projecting from each side of the head strain food, including algae, tiny animals and plant debris from the water. Only a few species of black flies bite people.

While we two-legged denizens of the North Country pride ourselves on being hardy and adaptable to the vicissitudes of Jack Frost, we don’t hold a candle to the intrepid six-legged critters that prowl the streams of winter.

Michael J. Caduto is a writer, ecologist and storyteller who lives in Reading. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.